Hello everyone and a special thank you to everyone who has subscribed! If you are just finding this, welcome! I am so glad that you all are here. 💗

If you are a new email subscriber (hello!), you can access previous posts and resources through the Substack app or on your desktop via Substack website.

First a nod to the title of this newsletter, which comes from Seattle author Ken Mochizuki who has written many wonderful books including Baseball Saved Us about baseball players in Japanese-American incarceration camps during World War II.

Dark days are upon us. Those of us who study history know what we are experiencing is not new. But, it doesn’t make it any easier.

Scholar and educator Gholdy Muhammad writes about the importance of joy in our teaching. And, I like to think that holding space for joy, whenever possible, is a way to rebel and resist too, especially in these times.

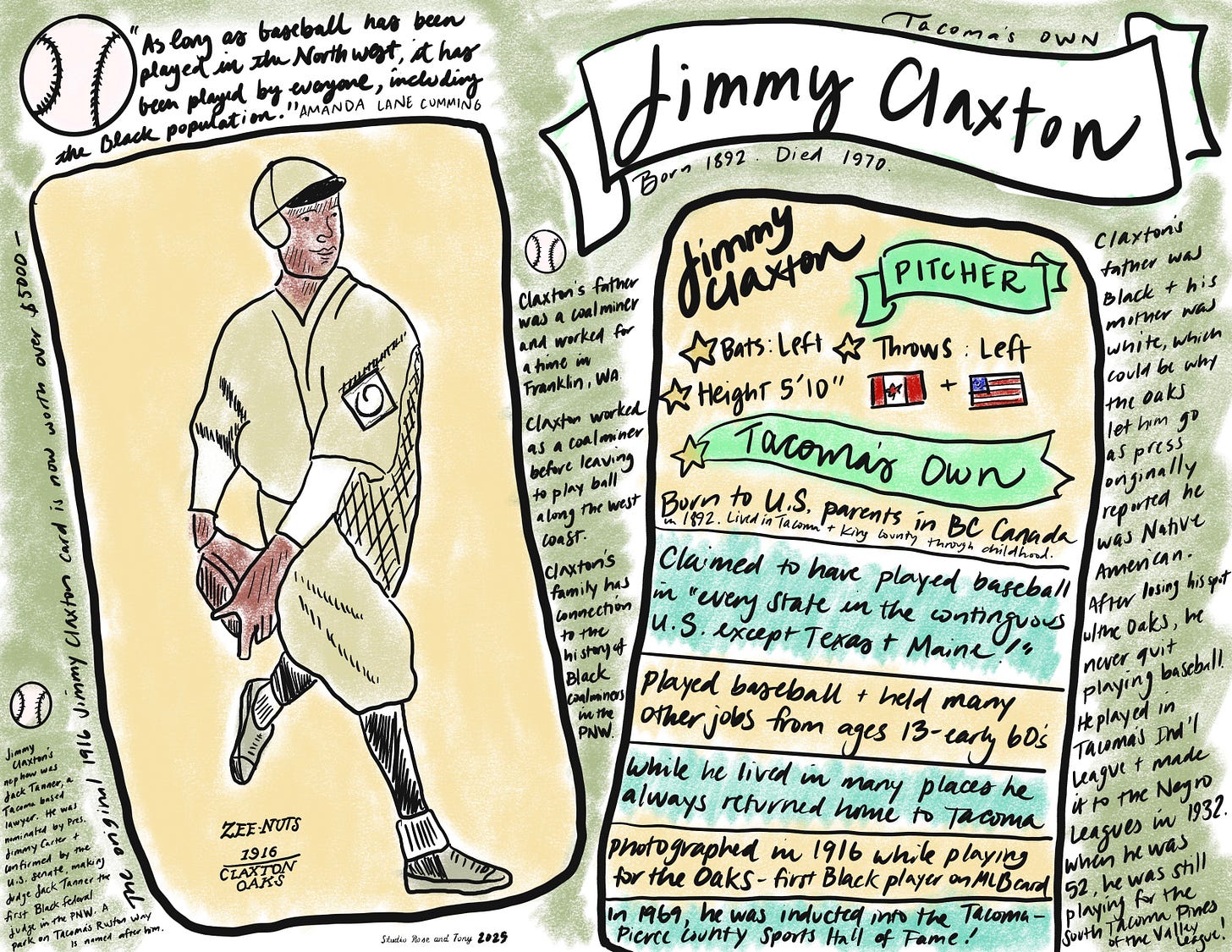

Given that many people are taking comfort in baseball’s opening day this week, I thought I would bring a little baseball to you all for your classrooms or trivia nights. For our collective resistance. To do this, we will learn about Tacoma’s own, Jimmy Claxton. Who is Jimmy Claxton you ask? Well, he is the first Black baseball player to have a major league baseball card!

I grew up with parents who were wholly uninterested in professional sports. My dad claimed that the sports gene his older brothers shared, skipped right over him. I was pretty convinced the gene skipped over me as well. When I was in the 3rd grade, my reading teacher was an avid sports fan. One time, she gave us the assignment to select our own chapter books for a unit. Her only criteria: it had to be about sports. I was in a total panic. What the h-e-double hockey sticks was I going to read about???

But, despite my lack of professional sports engagement, I have always had an appreciation of baseball. I loved the pace of it… being outside… I played baseball a lot in the yard with my mom when I was little, and later my younger brother. And, I grew up with some great baseball movies, including of course, the Sandlot (“You’re killing me, Smalls!”) and A League of Their Own (“There is no crying in baseball!”).

So, with the opening of baseball season, honoring joy while we navigate this darkness, and acknowledging the very interesting and important history of baseball in the Pacific Northwest, I bring you this week’s resource. I am able to do this with the help of my good friend, Michael Bowman (Lil Mikey B), who deeply loves baseball. He double checked this post for me and was also a HUGE help with the content.

At the bottom of this page, you will find the downloadable pictorial, information about Jimmy Claxton’s life, and a bit of writing by Michael Bowman about why baseball– especially community and semi-pro baseball– is so important in the history of community identity, race, and class in the PNW. All materials you can use with your students, or use to simply enjoy learning more about this bit of history.

In closing, I would like to share that I, like you readers, know everything is political. I take sweet revenge in these times teaching about “America’s Pastime” in a subversive way. I mean, it’s just a baseball card, right? If someone challenges me and cries - “There is no DEI in baseball!” - I imagine my innocent retort: “What do you mean? How can a little baseball card be political? Are you telling me that America’s Pastime is political?!” (Imaginary pearl clutch.) Which, of course, it is.

With that, onward.

Guest Contributor: Michael Bowman

I remember watching the 9-part Ken Burns Baseball documentary while in high school in 1994. Even though I had loved playing baseball as a kid and going to minor and major league games, Ken Burns’ series helped my 18-year old self think about how professional baseball was woven into the fabric of American histories of race, class, and national identity. Thirty years later, I think Burns’ argument holds up, and newer community-based histories give us glimpses into how this manifested at very local levels. Over the course of the late 19th through the mid-20th century, hundreds of local teams across Washington organized themselves into industrial leagues, semi-professional city leagues, barnstorming teams, and community teams. In almost every Washington town or community newspaper during the summer months, you were more likely to read about the Bellingham Model Truck Boosters, the Everett Sea Gulls, the Washington Browns, or the Wapato Nippons than the New York Yankees, St. Louis Cardinals, or the Kansas City Monarchs. Teams and leagues across the PNW pushed and pulled on national and local race-class politics.

Jimmy Claxton’s career is an example of his continual negotiations of local and national racial classification. As historian Amy Essington shows in the first chapter of The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast, Jimmy Claxton’s race on the U.S. Census went from “white” (1900), to “mulatto” (1910), to “black” (1920), while his World War I registration card identified him as “Ethiopian.” It is not exactly clear how Jimmy Claxton appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle in the spring of 1916 as an “Indian southpaw” from the “Minnesota reservation” in an article about the Oakland Oaks’ latest signing, but one can imagine several plausible scenarios of racial negotiation.

Stories of the intersections of race, class, and baseball exist throughout the historical record. The Cherry Baseball team formed in Seattle in 1910 as a way for Nisei (second generation, Japanese-American) youth to proudly assert both American and Japanese Identities. About the same time, the Tulalip Indian School team organized weekend series against predominantly “white” Everett city and industrial league teams, as well as series against the Lummi in downtown Marysville. The Seattle Owls, a Black women’s team, played to thousands of fans at Sick’s Stadium as part of their consecutive state championships in 1938 and 1939, just as the growing Black Seattle population organized against Seattle racial orthodoxy off the field.

As a new baseball season approaches, in Major League stadiums as well as countless minor and semi-professional ballparks, I can imagine the various ways that baseball players and fans from across the Americas are negotiating our current historical moment. Baseball has always been– and will always be– political.

Pictorial:

Biographical Outline Notes:

Similarly to The Mighty Dandelion pictorial, this is a Project GLAD style pictorial. You often draw these lightly in pencil before teaching about the topic, and as you teach content to the students, record what you share on the anchor chart with ink/color.

Curricular Connections: After introducing this pictorial to students, and possibly in connection to other content from class, have students create their own “baseball card.” They could use a favorite book character or the biography of someone they are learning about. This could also be a part of a non-fiction unit where they study the information and text features of baseball cards as a way to write and/or identify these features.

Sources to Explore:

Book: Amy Essington, The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast

Short Video: Who is Jimmy Claxton?, MLB KO'd with Keith Olberman

Substack: Amanda Lane Cumming, “Ernie Tanner, Jimmy Claxton, and the World They Forged”

Website: Jimmy Claxton, Society of American Baseball Researchers

Website: Judge Jack Edward Tanner

Book: Out of print book but an excellent one and can be found online and in libraries: Lyle Kenai Wilson, Sunday Afternoons at Garfield Park: Seattle’s Black Baseball Teams 1911-1951

Book: Ty Phelan, Darkhouse: The Jimmy Claxton Story

The next posting will be on April 2, 2025. Sending care for the next couple of weeks.

I honestly loved everything about this post! Happy to be on your list and thanks for including important history along with reminding us of the importance of joy. Yes, the personal is the political--and vice versa. We forget!